Rethinking the Rule of 100

A Story to Begin With

Two investors walk into the same financial planning office.

The first is 28 years old, earning a decent salary but juggling a home loan, car EMI, and plans for a child’s education. The second is 62, recently retired, debt-free, with accumulated savings and a steady pension.

According to the Rule of 100, the younger investor should aggressively invest in equities, while the older one should sharply reduce stock exposure. But when you look at their real financial lives, the picture feels counterintuitive. The younger investor cannot afford large losses, while the retired investor may actually have the stability to ride out market volatility.

This disconnect raises an important question:

Should age alone determine how much investment risk you take?

That question sits at the heart of this article.

The Rule of 100 – Asset Allocation by Age

When it comes to investing, one of the most common questions people ask is:

How much should I invest in equities and how much in safer assets?

To simplify this decision, financial planners have long relied on age-based formulas—the most popular being the Rule of 100.

At first glance, the rule seems logical and easy to follow. But does it truly reflect how real people earn, save, and spend today? Let’s take a closer look.

What Is the Rule of 100?

The Rule of 100 is a basic guideline used to determine asset allocation based on age.

Formula:

100 − Your Age = Percentage of your portfolio invested in equities

The remaining portion is allocated to bonds, debt instruments, or other relatively low-risk assets.

Simple Examples

- Age 30

- 70% in stocks

- 30% in bonds/debt

- Age 50

- 50% in stocks

- 50% in bonds/debt

The Logic Behind the Rule

The rule is built on a straightforward assumption:

risk tolerance declines with age.

Younger investors are expected to have:

- Longer investment horizons

- More time to recover from market downturns

Older investors, on the other hand, are assumed to:

- Prefer stability over growth

- Focus on capital preservation and steady income

This thinking made sense decades ago—but markets, careers, and lifespans have changed.

Why the Rule Evolved: Rule of 110 and Rule of 120

As life expectancy increased and inflation became a bigger threat, financial advisors began adjusting the formula.

Rule of 110

110 − Age = Equity allocation

- Age 30 → 80% equities

- Age 50 → 60% equities

This version recognizes that:

- People are working longer

- Retirement needs are larger

- Equity growth is crucial to beat inflation

Rule of 120

120 − Age = Equity allocation

- Age 30 → 90% equities

- Age 50 → 70% equities

This rule is typically suggested for investors with higher risk tolerance or those relying heavily on equity markets for long-term wealth creation.

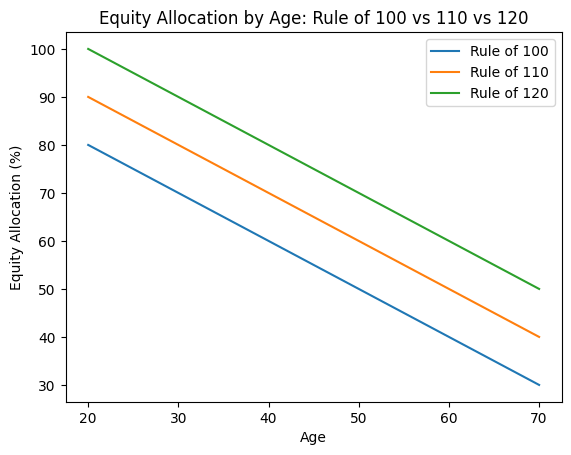

A comparison of Rule of 100 vs Rule of 110 vs Rule of 120 is shown in the chart below:

What the Chart Shows

- X-axis: Investor age

- Y-axis: Suggested equity allocation (%)

Three declining lines represent:

- Rule of 100 (most conservative)

- Rule of 110 (moderate)

- Rule of 120 (most aggressive)

Key Takeaways:

- All three rules reduce equity exposure linearly with age

- The difference between rules becomes more pronounced at younger ages

- Even at age 60–70, Rule of 120 still suggests meaningful equity exposure, reinforcing the inflation-risk argument

The Big Problem With All These Rules

Despite their popularity, the Rule of 100, 110, and 120 share one major flaw:

They assume age alone determines risk capacity.

In reality, age tells only part of the story.

A Contrarian Perspective: When the Rule Breaks Down

Younger Investors Aren’t Always Risk-Takers

Many young investors face:

- Lower incomes and limited savings

- Home loans, car EMIs, and education expenses

- Small emergency buffers

For them, a sharp market fall can cause real financial stress. Even though time is on their side, their ability to absorb losses may be limited. In such cases, aggressive equity exposure can do more harm than good.

Older Investors May Have Higher Risk Capacity

Ironically, many older or retired investors:

- Are free from major financial obligations

- Have accumulated wealth, pensions, or rental income

- Can emotionally handle short-term volatility

For them, maintaining meaningful equity exposure may actually be necessary to protect purchasing power against inflation.

The Real Question: Risk Tolerance or Risk Capacity?

This is where most age-based rules fall short.

- Risk tolerance is how comfortable you feel with volatility

- Risk capacity is whether your finances can survive a downturn

Risk capacity depends far more on:

- Cash flows

- Liabilities

- Financial security

- Emergency reserves

—not just your age.

Final Thoughts

The Rule of 100 and its modern variations are useful starting points, not formulas to follow blindly.

Smart asset allocation requires balancing:

- Age

- Income stability

- Financial responsibilities

- Long-term goals

- The ability—not just the willingness—to take risk

In investing, simplicity helps.

But context matters even more.

What Do You Think?

- Should age alone determine how much risk an investor takes?

- Have your financial responsibilities increased or reduced your ability to invest in equities?

- For younger investors with EMIs, is aggressive equity allocation practical—or risky?

- Should retired investors reduce equity exposure simply because of age?

- Which matters more: risk tolerance or risk capacity?

- Do you follow the Rule of 100 (or 110/120), or have you created your own approach?

👉 Share your views—your experience may help others rethink how they invest.